Well, keep in mind that the Riverlands aren’t just a nexus point for the Stormlands and the Iron Islands – we know that that the Kings of the Rock “warred against the many kings of the Trident,” we know that “the lords of the Reach sent iron columns of knights across the Blackwater whenever it pleased them,” and we know two kings from the Riverlands invaded the Reach during the reign of Gyles III.

Dorne was another important nexus – hence the political importance of the marcher lords in both the Reach and the Stormlands and the fierce independence of the mountain lords of Dorne – both before and after the arrival of the Rhoynar. Dorne’s role was to force both the Reach and the Stormlands to keep an eye on their southern borders and to pounce on any sign of over-stretch or weakness: Garth VII had to be nimble as hell to fight the Fowler Kings and the Ironborn at the same time, but when Gyles III looked to conquer the Stormlands, three Dornish kings invaded him; likewise, when Arlan III conquered the Riverlands, the moment he died the Dornish launched invasions over the Boneway.

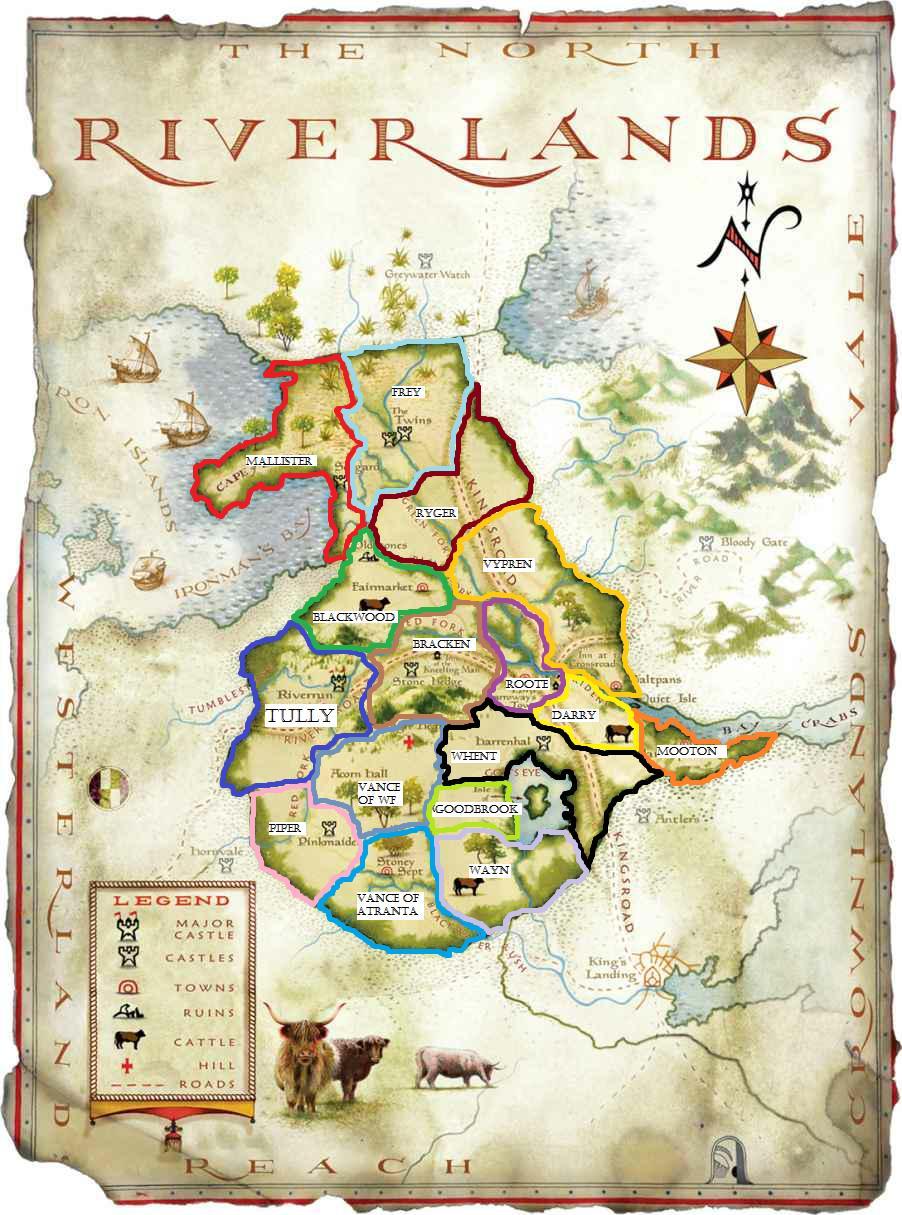

So I would argue there are several levels that the Great Game operated on: there’s the Riverlands nexus (which includes the Westerlands, the Stormlands, and occasionally the Reach and the Vale, and would later include the Iron Islands), the Westerlands/Reach nexus, the Reach/Stormlands nexus, and the Reach/Dorne/Stormlands nexus. And all of these nexii were going on at the same time, making for a very complicated conflict.

In terms of the importance of the Rhoynar, we don’t know enough – we get a sense that Nymeria’s uniting of Dorne allowed them to successfully hold off invasions by the Stormlands and the Reach, and we get a few accounts of invasions of the Reach and the Stormlands by the Dornish, but most of that is during the pre-Martell phase.