Well, it’s more efficient from a production standpoint – which is one reason why families did try to marry neighbors when possible – but it’s not necessarily easier. There’s no guarantee that neighbors will produce children at the right time and right gender sequencing for those marriages to take place, there’s always the tradeoff between marrying into a smaller neighboring landholding vs. a bigger landholding that’s not contiguous, and there’s neighbors on more than one side, and so on.

However, I’d say the biggest issue is the variable quality of land.

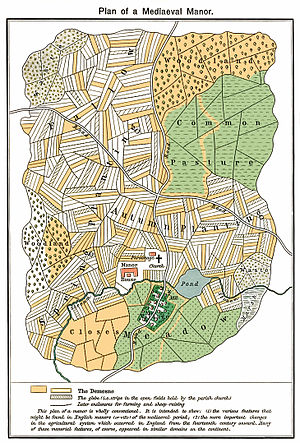

One of the reasons why manors divvied up land in strips as opposed to any other shape or configuration is they were trying to make sure that every family got a share of “bottomland” and upland, so that you didn’t have a situation in which some families couldn’t support themselves on their assigned plots.

Well, the same issue applies when it comes to marriages: your neighbor’s land might not be of equal quality to your land, whether that’s because it doesn’t get as much water or the soil pH is off or it’s rocky or whatever. In that case, it’s better to marry into a famiy that’s non-contiguous but has high-productivity land.

And the same principle goes all the way up the class scale, just on different issues: your neighbors’ manors might not bring in as much of an income as manors on better land somewhere else, and so on.