2/2 this can pretty easily be seen in history where regions with many of the same qualities and resources either advance and grow in wealth and development or remain stagnant. You had touched on some of this in your regional development pieces, “In Dorne we all band together…”, something like that. I know its very vague and has to do with symbols and emotional stats and so on. Still seems important in relation to how states and so on grow or don’t. Thanks

Ultimately the management of feudal manors was a political process by which relations between lord and peasant were worked out, and it could be a very antagonistic or a more symbiotic one depending on the political skills of both sides (or even mediators like royal judges or local clergymen).

While law and political culture gave lords the upper hand (although not entirely), pushing too hard and too fast would cause unrest and disruption, so a lot of aspects of noble culture were designed to give noblemen the skills necessary to manage their tenants and workforce without provoking resistance: adhering to noblesse oblige was a good way of gaining popular goodwill through symbolic displays of generosity (donating hand-me-downs to the poor, or conspiciously giving alms/tithing at church, etc.), being able to gracefully condescend to your lessers was important to ensure that social interactions between noble and peasant didn’t give rise to contempt or resentment.

On the flip side, peasants had one important trump card that made up for some of their massive disadvantages when it came to legal, political, and sociocultural status: they were the only workforce around. Peasants could use various means of direct action to resist actions of their landlords: they could strike as workers by refusing to labor on the lord’s land, they could strike as tenants by withholding their rent payments, they could get violent (often by setting gathered crops or fixed improvements on fire, or breaking fences and other symbolic violations of noble prerogatives, or beating the crap out of the bailiffs and reeves or burning down the manorial court), or they could turn to the courts. There were quite a few cases where individual peasants and whole village would hire lawyers and sue their landlords, especially in cases where there was a dispute over whether tenants were free peasants or serfs.

But on both sides, there were always important tensions between peace and profit, and between tradition and innovation. To quote myself for a second:

Almost by definition, the major source of income of a noble family is rent income from their lands, and rents were overwhelmingly set by custom and tradition. This meant that most nobles were living on something like a fixed income, which meant they were very vulnerable to changes in prices. Crop failures, rebellious peasants demanding wage increases, competition from foreign countries, all of these things could seriously negatively affect the bottom line.

This meant that attempts to raise rents could be resisted by peasants through the law, pointing to manorial rolls or copies of tenancy agreements (or even the memory of the oldest person around) as proof that their lord was violating their ancient rights. At the same time, there were also examples of lords who went looking for feudal taxes, privileges, or labor that had been previously waived (a strategy that lords could and often did use to decrease tensions), and insisting on enforcing their ancient rights.

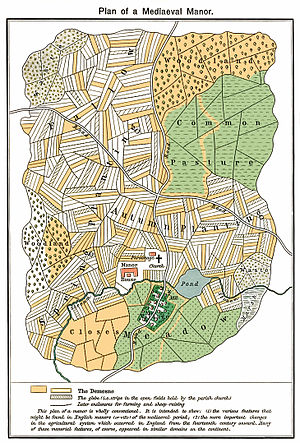

So, how do lords pursue economic development in that situation? Well, if one had the capital, one could invest in infrastructure: draining fenland or clearing forest would give the lord additional land that they could now settle with new tenants (and since these were legal blank slates, the lord wasn’t bound by the old terms of service), building mills or other processing industries would create new ways to extract income from one’s tenants and increasing the value-added of the good produced by the manor, investing in new farming techniques on the lord’s land (as opposed to the land that was leased to tenants) would increase the productivity of that land.

In addition to techniques, the most historically significant change a lord could make would be to change what they grew. In the early modern period, with the advent of the commercial revolution, many English landlords shifted from growing traditional cereal crops to pasturing sheep to export their wool to the Netherlands, despite the massive disruption to agricultural labor markets. To quote from Utopia:

But yet this is not only the necessary cause of stealing. There is another, which, as I suppose, is proper and peculiar to you Englishmen alone. What is that, quoth the Cardinal? forsooth my lord (quoth I) your sheep that were wont to be so meek and tame, and so small eaters, now, as I hear say, be become so great devourers and so wild, that they eat up, and swallow down the very men themselves. They consume, destroy, and devour whole fields, houses, and cities. For look in what parts of the realm doth grow the finest and therefore dearest wool, there noblemen and gentlemen, yea and certain abbots, holy men no doubt, not contenting themselves with the yearly revenues and profits, that were wont to grow to their forefathers and predecessors of their lands, nor being content that they live in rest and pleasure nothing profiting, yea much annoying the weal public, leave no ground for tillage, they inclose all into pastures; they throw down houses; they pluck down towns, and leave nothing standing, but only the church to be made a sheep-house.

See, along with the shift to wool exports came a legal movement in the 16th century to enclose the formerly common lands of manors (one of those pesky traditional rights that peasants kept insisting upon) and turning them into the lord’s property. This was so hugely disruptive that it led to riots starting in the mid-16th century, but lords with a sturdy enough backbone and quiet enough conscience were able to bull ahead despite resistance from King, Parliament (from 1489 to 1639) and their own people, so lucrative were the profits.