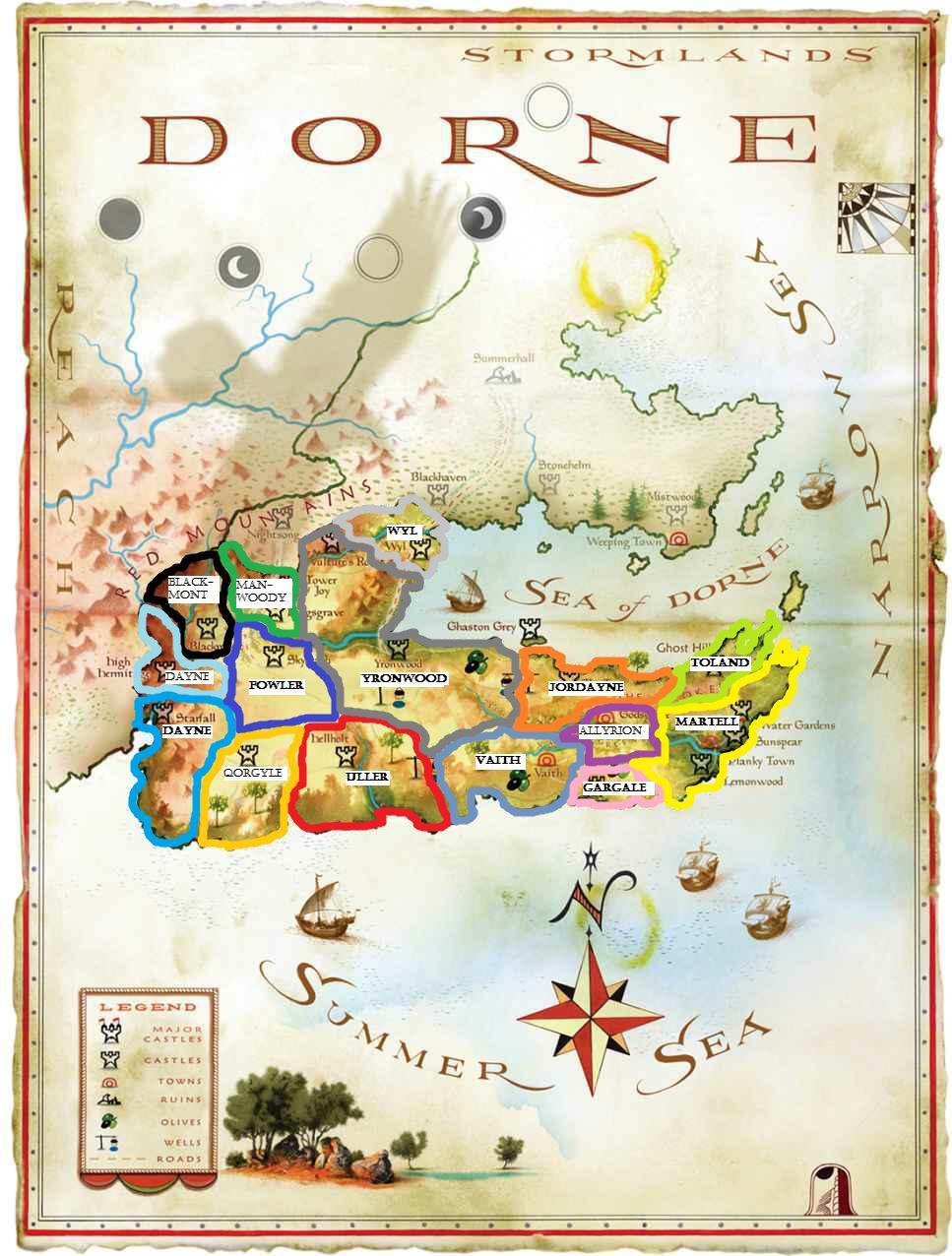

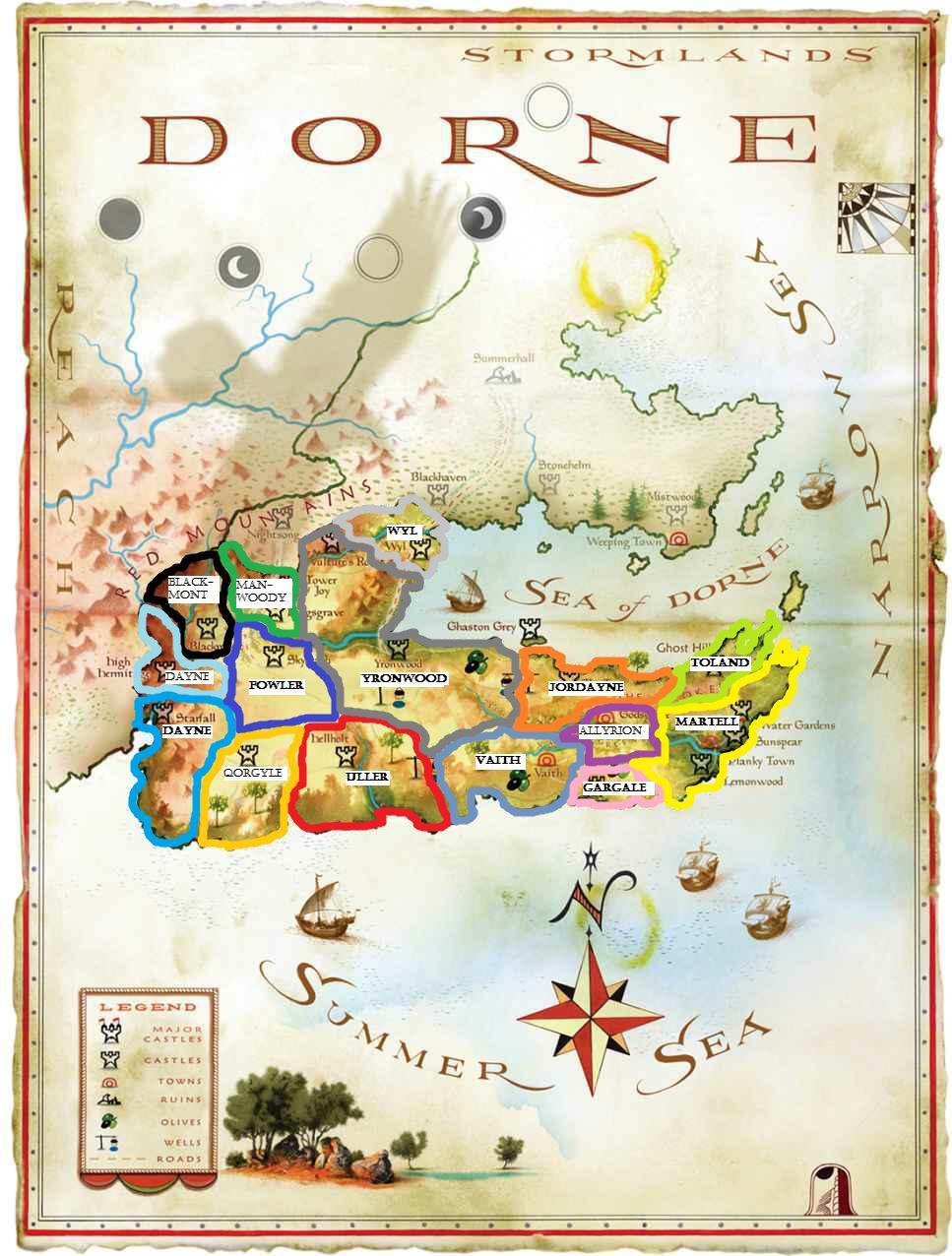

Politics of the Seven Kingdoms: Part IX (Dorne)

Hey folks! After a long delay on my part, I’ve combined and edited together the three parts of my Politics of Dorne essay, which is now up on Tower of the Hand…

Just a backup in advance of the detumblring

Politics of the Seven Kingdoms: Part IX (Dorne)

Hey folks! After a long delay on my part, I’ve combined and edited together the three parts of my Politics of Dorne essay, which is now up on Tower of the Hand…

I wrote a much longer version of this, but delted it because I was getting repetitious, so here’s trying for something more concise:

William I: did face quite a bit of opposition from the remaining Saxon Earls and the heirs of Harold Godwinson and the remaining members of the House of Wessex, but also from the Count of Boulogne (a former ally of his during the Conquest who was pissed off at the division of the spoils), King Sweyn of Denmark, King Malcom III of Scotland, and in his Continental holdings from King Phillip of France. His foreignness definitely played a role in the Saxon rebellions, but you have to put it into a complicated international context where Saxons might ally with Danes or Scots against Normans and other Saxons ally with the Normans against the Danes and Scots.

James I: Not really, except for conflict between James and Parliament over James’ desire to be recognized as King of Great Britain. James’ Scottishness was outweighed by the fact that he was the clear successor to Elizabeth and supported by her administrators, and also the fact that he was a Protestant (especially in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot). Not that there weren’t conflicts with the new King, but they usually had to do more with royal debt, taxation, and the prerogatives of Parliament vs. the King.

William III: I cannot emphasize how much this depends on where you’re talking about. William and Mary’s accession to the throne and the deposing of James II was way more popular in England than it was in Scotland or Ireland, hence why the various Jacobite revolts were based in Scotland or Ireland with only a minority of support in England. And this political conflict was directly linked to religious identity: James II’s Catholicism and support for Catholics in government was a major reason why he found support in Catholic areas of Scotland and Ireland, whereas William III’s Protestantism made him more popular in England. Indeed, when William landed in England as part of the “Glorious Revolution,” the motto on his banner (”Pro Religione et Libertate”) was understood by all to be referring to Protestant religion and Protestant freedom.

George I: more so than William III. William was Dutch, but his mother and wife were English and he himself could speak English, and his wife was an English Queen, so that militated against any such reaction. George’s English connections were more remote, and at least for the early part of his reign George couldn’t speak English. While this wasn’t a direct cause of the two major Jacobite revolts during his reign, the sense that George was a foreign monarch did probably contribute, at the very least to the increased participation of English Tories in the Jacobite uprising of 1715. However, later Jacobite risings in 1719 and 1745 really only drew their support from Scotland, suggesting it was something of a transient phenomenon.

Good question!

I think the answer is to look at where and how the North has defeated the Ironborn on land:

It was too late for that now, however. Theon had no choice but to lead Asha to Ned Stark’s solar. There, before the ashes of a dead fire, he blurted, “Dagmer’s lost the fight at Torrhen’s Square—”

“The old castellan broke his shield wall, yes,” Asha said calmly. “What did you expect? This Ser Rodrik knows the land intimately, as the Cleftjaw does not, and many of the northmen were mounted. The ironborn lack the discipline to stand a charge of armored horse. Dagmer lives, be grateful for that much. He’s leading the survivors back toward the Stony Shore.”The sea was closer, only five leagues north, but Asha could not see it. Too many hills stood in the way. And trees, so many trees. The wolfswood, the northmen named the forest. Most nights you could hear the wolves, calling to each other through the dark. An ocean of leaves. Would it were an ocean of water.

Deepwood might be closer to the sea than Winterfell, but it was still too far for her taste.If it were me, I would take the strand and put our longships to the torch before attacking Deepwood…

“My queen,” said Tristifer, “here we have the walls, but if we reach the sea and find that the wolves have taken our ships or driven them away …”

“… we die,“Something flew from the brush to land with a soft thump in their midst, bumping and bouncing. It was round and dark and wet, with long hair that whipped about it as it rolled. When it came to rest amongst the roots of an oak, Grimtongue said, "Rolfe the Dwarf’s not so tall as he once was.” Half her men were on their feet by then, reaching for shields and spears and axes. They lit no torches either, Asha had time enough to think, and they know these woods better than we ever could. Then the trees erupted all around them, and the northmen poured in howling. Wolves, she thought, they howl like bloody wolves. The war cry of the north. Her ironborn screamed back at them, and the fight began.

And we had other help, unexpected but most welcome, from a daughter of Bear Island. Alysane Mormont, whose men name her the She-Bear, hid fighters inside a gaggle of fishing sloops and took the ironmen unawares where they lay off the strand. Greyjoy’s longships are burned or taken, her crews slain or surrendered…

The Ryswells and the Dustins had surprised the ironmen on the Fever River and put their longships to the torch….

Harren died at Moat Cailin. One of the bog devils shot him with a poisoned arrow…

In Moat Cailin he had taken to wearing mail day and night. Sore shoulders and an aching back were easier to bear than bloody bowels. The poisoned arrows of the bog devils need only scratch a man, and a few hours later he would be squirting and screaming as his life ran down his legs in gouts of red and brown.

Behind him were the camps, crowded with Dreadfort men and those the Ryswells had brought from the Rills, with the Barrowton host between them. South of Moat Cailin, another army was coming up the causeway, an army of Boltons and Freys marching beneath the banners of the Dreadfort. East of the road lay a bleak and barren shore and a cold salt sea, to the west the swamps and bogs of the Neck, infested with serpents, lizard lions, and bog devils with their poisoned arrows.

While the Ironborn are stronger at sea, the North is stronger on land, and the problem for the Ironborn is that the North is nothing but land. The Ironborn don’t have the numbers to occupy the North, and their soldiers don’t have the training or equipment needed to fight the greenlander way.

If it I was giving strategic advice, I would tell the Northmen to surrender the coasts after carrying off everything edible and burning the rest, retreat into the interior, let the Ironborn spread themselves thin by trying to occupy the North.

Then once the Ironborn are over-extended and as far from the sea as can be arranged, ambush their patrols and attack any force on the march, besiege every castle and starve them out, burn their ships and cut them off from the sea.

Good question!

So here’s what we know about keyholders:

“Archmaester Matthar’s The Origins of the Iron Bank and Braavos provides one of the more detailed accounts of the bank’s history and dealings, so far as they can be discovered; the bank is famous for its discretion and its secrecy. Matthar recounts that the founders of the Iron Bank numbered three-and-twenty; sixteen men and seven women, each of whom possessed a key to bank’s great subterranean vaults. Their descendants, whose numbers now exceed one thousand, are known as keyholders to this day, though the keys they display proudly on formal occasions are now entirely ceremonial. Certain of the founding families of Braavos have declined over the centuries, and a few have lost their wealth entirely, yet even the meanest still cling to their keys and the honors that go with them.

The Iron Bank is not ruled by the keyholders alone, however. Some of the wealthiest and most powerful families in Braavos today are of more recent vintage, yet the heads of these houses own shares in the bank, sit on its secret councils, and have a voice in selecting the men who lead it. In Braavos, as many an outsider has observed, golden coins count for more than iron keys.”

In the first place, the extinction of family lines doesn’t seem to be a problem, given their 43-fold growth. In the second place, to the extent that it’s a problem it’s been solved by allowing the wealthy and powerful to buy shares of the bank’s stock, and thus becoming voting members.

There’s several factors:

Good question!

Yes, absolutely the Land Bank could be built without the canal, it’s just that the two are complementary, with the Bank providing credit for the canal and canal revenue providing a steady stream of capital for the bank.

Most likely, they’d need permission just as the Lannisters probably would.

Now, it’s possible that if the Land Bank stuck to just being a sub-treasury system which didn’t issue loans but only IOUs for crops that were only good in the Reach, they might be able to get away without needing royal permission unless some bright spark in the Master of Coin’s office realized that those IOUs were effectively money.

Good question!

So here’s the relevant passage:

“He is writing each a binder. If their ships are lost in a storm or taken by pirates, he promises to pay them for the value of the vessel and all its contents.”

“Is it some kind of wager?”

“Of a sort. A wager every captain hopes to lose.”

“Yes, but if they win …"

“… they lose their ships, oftimes their very lives. The seas are dangerous, and never more so than in autumn. No doubt many a captain sinking in a storm has taken some small solace in his binder back in Braavos, knowing that his widow and children will not want.” A sad smile touched his lips. “It is one thing to write such a binder, though, and another to make good on it."

Emphasis mine there. The old man in question has been refusing to honor maritime insurance contracts – which the Braavosi call “binders” – and probably a widow or widows who’ve been screwed over “came to the House of Black and White and prayed for the god to take him.”

I don’t know whether you need permission to build a road (as opposed to building a castle, where you definitely do), but my guess is that House Rowan would need the permission (or more likely, a license) from their liege lord to build on lands other than those of themselves and their own vassals.

So in the case of a ringroad meant to connect the Ocean Road to the Rose Road by way of Goldengrove, at the very least you’re going to need the permission of the Oakhearts of Old Oak, quite possibly the Cranes of Redlake (depending on how far south their lands go), and definitely the Caswells of Bitterbridge, and given how large those open plains are I would guess some more houses.

Good question (and definitely send me a link to the map when you’re done)!

Re the Glovers and Tallharts: I would lean to separate, since they still have the right to tax and levy military support from those lands, and GRRM has talked about landed knights potentially being quite powerful. Maybe color them as alternating stripes between Stark grey and their own house color?

Re Stony Shore and Sea Dragon Point: WOIAF says that the Stony Shore was ruled by House Fisher, who became vassals of the Kings of Winter. We don’t know whether they survived the Ironborn incursions, but I would guess the lands are held by some vassal. Sea Dragon Point was once ruled by the Warg Kings before the Starks conquered them, but we don’t know who rules it now and whether they survived the Ironborn either.

Re the Mountain Clans: definitely separate. They are vassals of the Starks, but among the more independent given their distance and traditions.

Almost all of us start from some place of privilege in some way – Gendry may be lower class than Tyrion, but Tyrion has a disability and Gendry doesn’t – so Jon Snow certainly has class advantages that many others in the Night’s Watch don’t, but he’s definitely below LC Jeor Mormont or Ser Alliser Thorne or Ser Denys Mallister

Moreover, social mobility doesn’t just apply to the very bottom and the very top; it’s a spectrum that goes all the way up (and all the way down, when we’re talking about downward mobility). So Jon Snow starts out as a bastard who will never inherit land nor title and becomes Lord Commander of the Night’s Watch and will probably end up as (one of) the savior(s) of humanity. Hard to top that.

As for Gendry, he starts as a bastard orphan, becomes an apprentice blacksmith, and is now a knight and has his own shop. That’s astonishing levels of social mobility for his society.